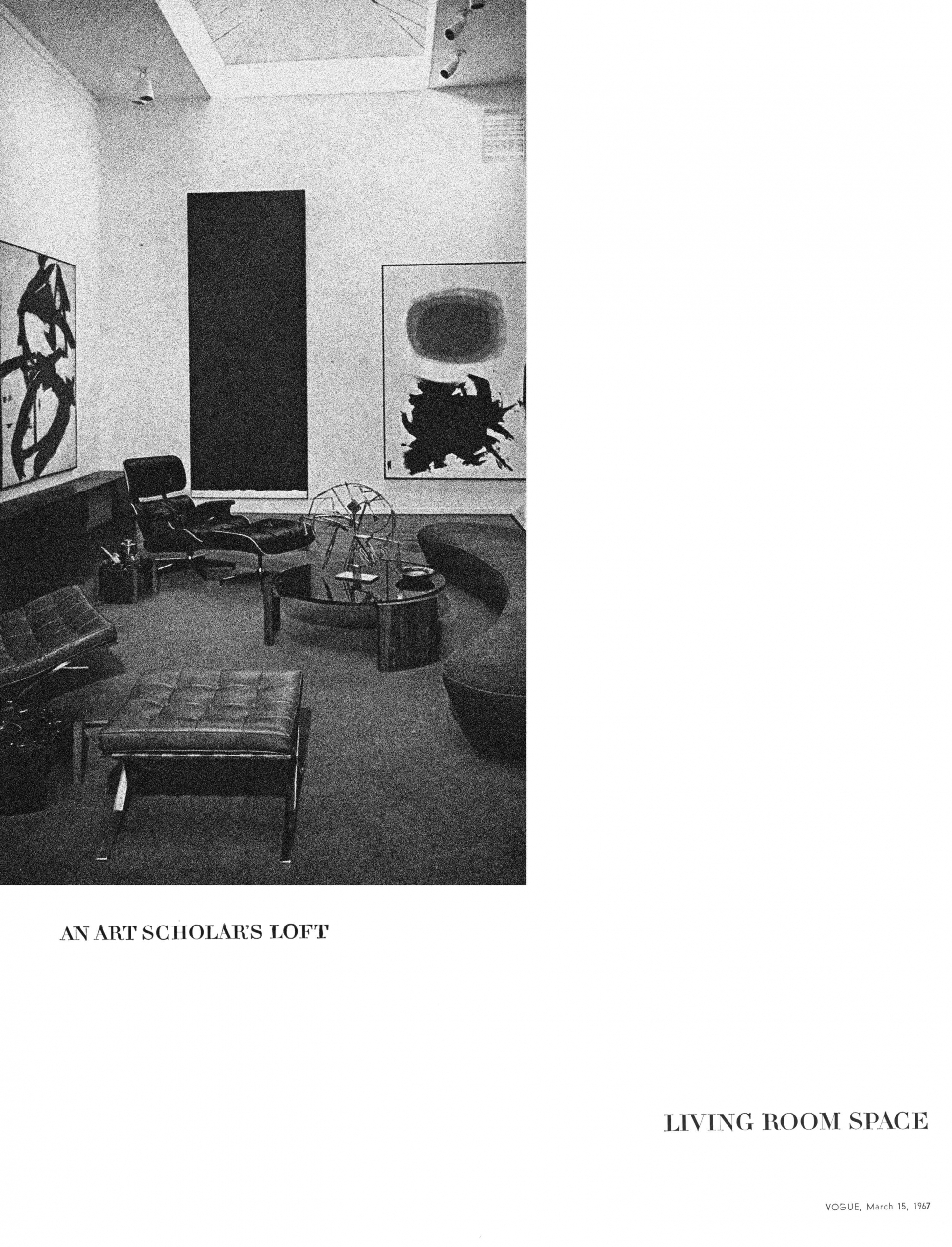

An Art Scholar's Loft

Annette Michelson

Introductory essay by

Robert McKenzie

Img:

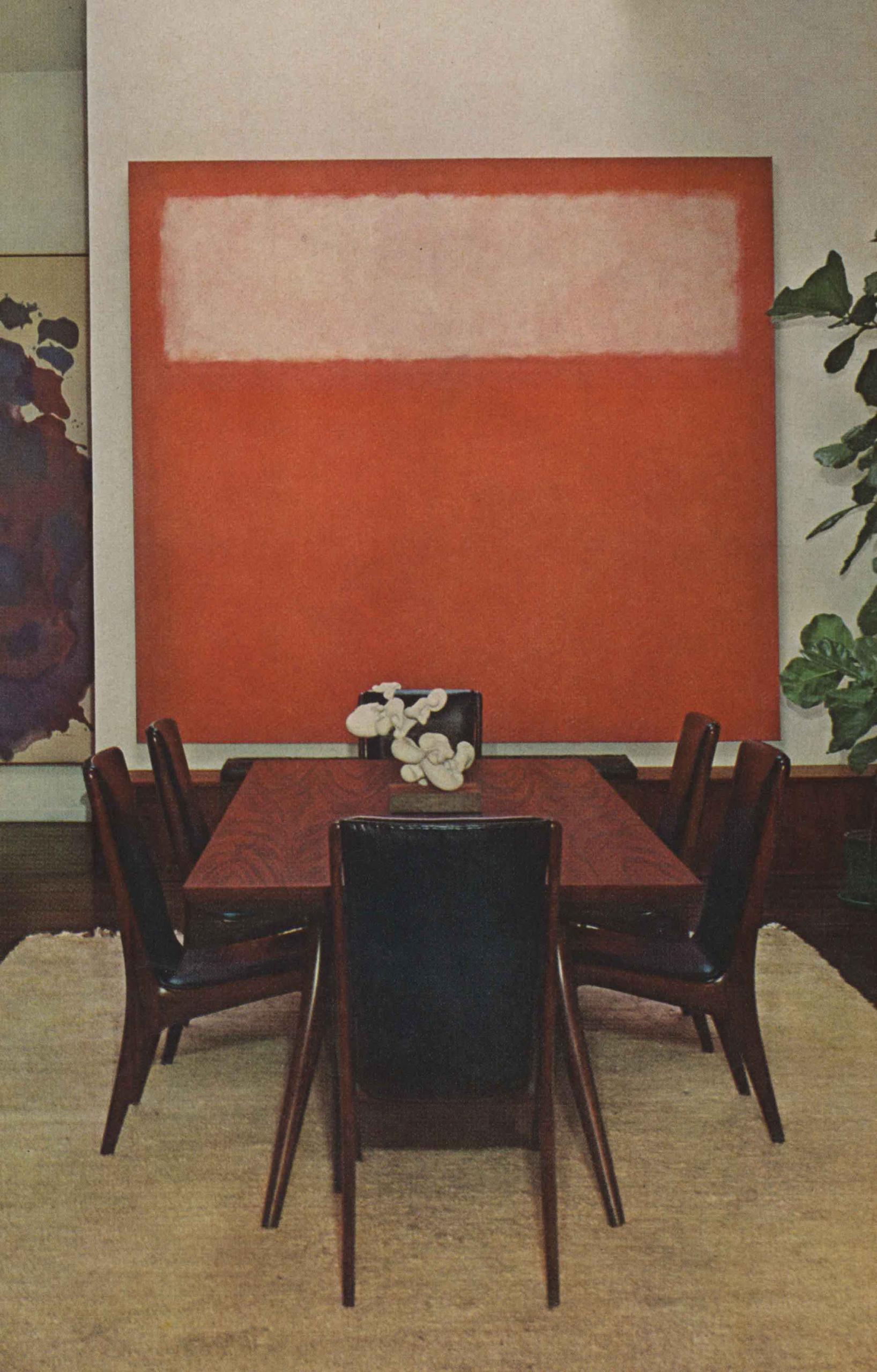

Professor Rubin in his office area, behind him a Kenneth Nolan painting.

Photo: William Grigsby, Vogue © Condé Nast

1.

Leonard Lauder in William S. Rubin, “A Curator’s Quest: Building the Collection of Painting and Sculpture of The Museum of Modern Art, 1967-1988,” Overlook & Duckworth, New York and London, 2011 p.6

2.

Email correspondence with the author November 29, 2017

3.

William S. Rubin, “A Curator’s Quest: Building the Collection of Painting and Sculpture of The Museum of Modern Art, 1967-1988,” Overlook & Duckworth, New York and London, 2011 p.20

4.

New York City Landmarks Designation report for 827-831 Broadway http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/2594.pdf (accessed Novemebr 28, 2017)

5.

Annette Michelsen, “Fashions in Living: An Art Scholar’s Loft: The New York Apartment of William Rubin.” Vogue, March 15, 1967 p.142

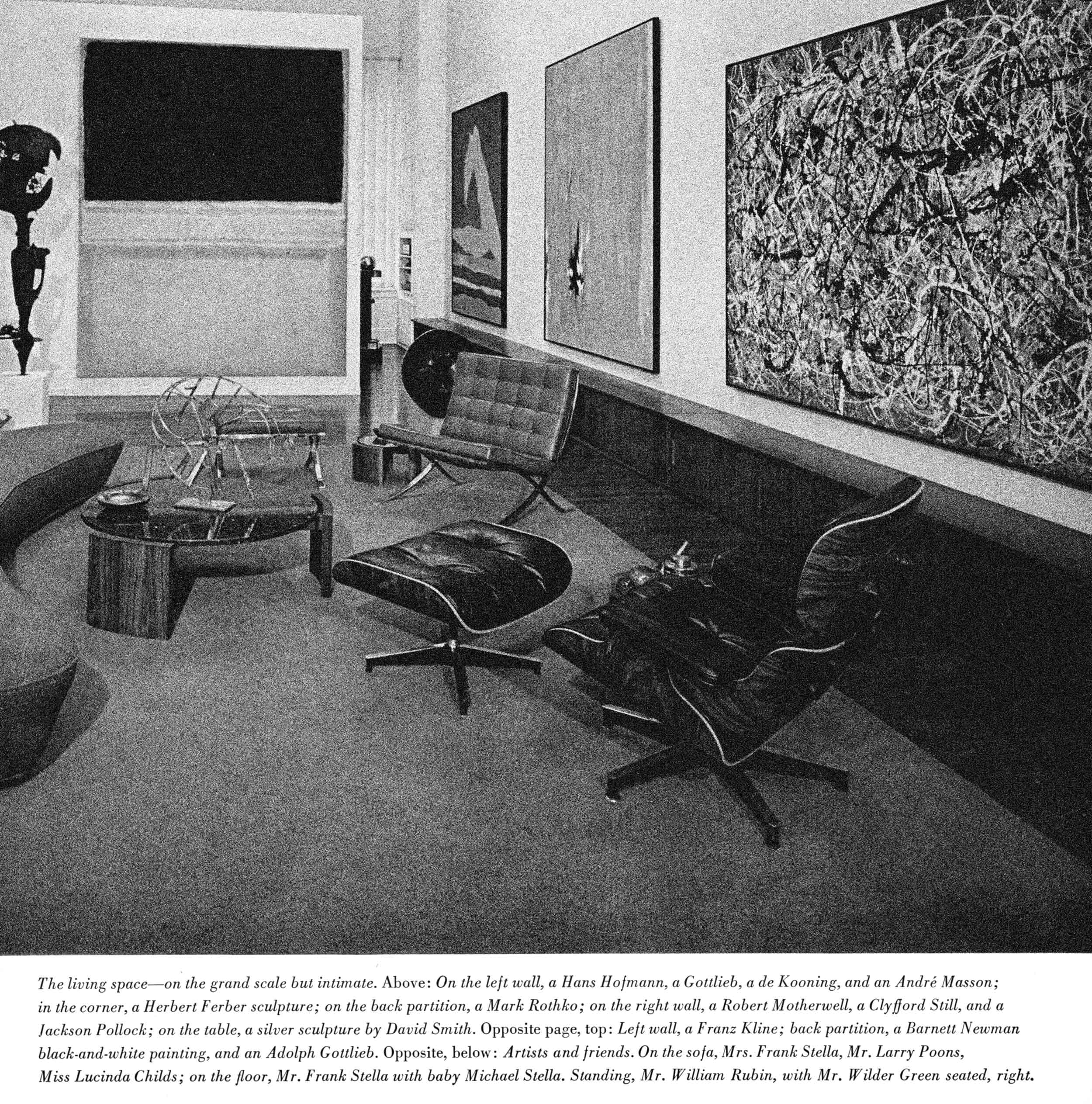

I In 1967, Vogue Magazine published a 10-page spread titled “An Art Scholar’s Loft: Light, Silence, and Space.” The numerous photos, some in black and white but most in saturated color, illustrated the art collection of William S. Rubin - a relatively unknown art history professor then teaching at Sarah Lawrence College. Leonard Lauder, a New York collector who would go on to donate an impressive group of Cubist masterworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, described the effect this article had on him: “That’s how I first learned about [Rubin]… I remember a remarkable photo of him in his loft in New York: Bill surrounded by a fabulous Jackson Pollock, a Franz Kline, works by David Smith, Larry Poons, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko. But it wasn’t just that these were the major artists of the time, these were the greatest works by each of them. I was immediately envious.” 1

The article had been commissioned by Barbara Rose, a young art historian who was hired by the magazine’s editorial director Alex Liberman to consult on art content. When asked many years later about the article, Rose commented that “I think [Rubin] thought it would make him seem glamorous.” 2 If we extrapolate from Lauder’s comments, people certainly took notice.

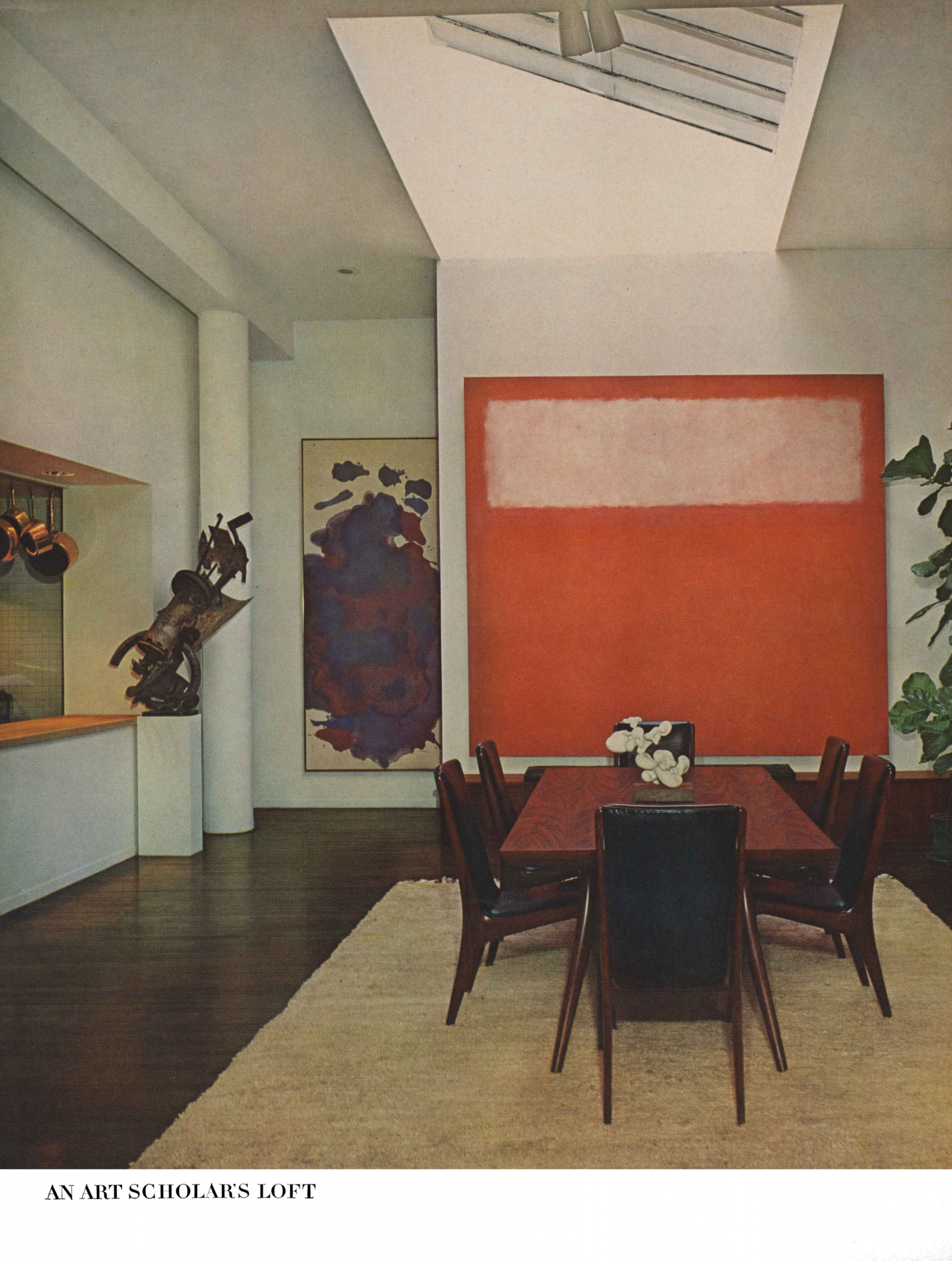

Social ties, rarely more than one or two steps removed from each other, criss crossed Rubin’s collection. Barbara Rose was married to the painter Frank Stella and one of Stella’s large copper-colored stripe-paintings was featured prominently in the photos of Rubin’s collection. Stella’s good friend Richard Meier had been responsible for the renovation of the loft. As Rubin later recalled, “I moved into a very large loft, which I had remodeled by Richard Meier, at that time a relatively unknown young architect but one who was friendly with vanguard painters.” 3 Willem De Kooning, Paul Jenkins, Jules Olitski, Herbert Ferber and Larry Poons had even had, at one time or another, studios in the same building as Rubin. 4 As the article in Vogue observed, Rubin, “installed his canvases and sculptures, living, so far as possible, amidst the artists who made them.” 5

The article was written by Annette Michelson, an American art and film critic who had recently returned to New York after a period of ten years in Paris working as a contributing editor for the New York Herald Tribune. During her time abroad, she had steeped herself in French criticism and theory, a proclivity that came to the fore when she launched the highly academic art journal October with art historian Rosalind Krauss. Her description of Rubin’s loft is a little highfalutin and enjoyably florid. While her words are ultimately laudatory, the hyperbole comes across as almost sarcastic. Michelson seems to critique Rubin as the contemporary embodiment of an emerging neoliberal impulse to conflate life and work.

Michelson is extraordinarily detailed in her contextualization of Rubin and his activities as a collector. The text is almost diagrammatic, describing the shape and form of Rubin’s artistic and social millieu and its intellectual parameters. In its specificity we are given an inkling of the limitations of the collector’s attention. By defining so carefully Rubin’s history and his current focus on American contemporary painting and sculpture, Michelson helps us to see just how much was beyond his purview. Any collection is ultimately limited to that which is within arm’s reach of the collector. Considering the propensity of history to develop lacunae, in this instance the absence of women and black and brown artists in art history, Michelson’s text might serve as an exposé of how white men came to dominate the Post-War art world. Art could be seen as the physical remains of a particular social group. Culture in general might be the collective shedding process of a society. Following this logic, if art and culture is made by everybody, the identification of who preserves it and how they do so and why they do so, is far more pertinent to history than what is selected and identified.

1.

William S. Rubin, “A Curator’s Quest: Building the Collection of Painting and Sculpture of The Museum of Modern Art, 1967-1988,” Overlook & Duckworth, New York and London, 2011 p.20

2.

MoMA Archives Oral history, W.Rubin. p.9 of 115. https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/archives/transcript_rubin.pdf (retrieved 28 November, 2017)

3.

Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, “Stanford’s Anderson Collection museum to feature trove of couple’s art,” LA Times, July 11, 2014 http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-ca-hunk-moo-stanford-anderson-collection-20140713-story.html (accessed 28 November, 2017)

I Shortly after the Vogue magazine article was published, Alfred Barr - the famed director of the Museum of Modern Art - offered Rubin a full-time job as a curator. While the Vogue magazine article may have been intended as Rubin’s coming out party, it was in fact the high-water mark of Rubin’s life as a private collector of contemporary American art. Rubin recalled many years later that his loft, “was no less than a small museum, and my interest in it only began to wane after 1967, as I faced the much larger and more exciting challenges of collecting for the Museum. I worked so hard and so late at the Museum that I saw little of my loft, and after about eight years I sold it for the cost of the improvements I had made to the space to the painter Larry Poons, bought an apartment, and dispersed much of my collection.” 1

Great collections often have fascinating and ghostly after-lives, and Rubin’s collection is no exception. Many of the works were sold through his brother Lawrence Rubin who was an art dealer. The Jackson Pollock drip painting “Mural on Indian Red Ground” from 1950 was sold to the Iranian Queen Farah Diba for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, the proceeds of which went towards a vacation home in the south of France. One of the Rothkos, “Untitled (Black Pink and Yellow over Orange),” 1953 was was sold in 1970 to Graham Gund, an architect and art collector based in Boston. Graham’s sister Agnes Gund purchased Rubin’s Hans Hofmann painting “Cathedral” 1959 and donated it to the Museum of Modern Art in his honor in 1991.

The largest number of works to remain together from the collection were the five paintings acquired by Palo Alto based business man “Hunk” Anderson and his wife “Moo.” Under the influence of Albert Elsen, an art historian at Stanford, the Andersons had turned their collecting interests to Abstract Expressionism. As Rubin tells it, “(a) friend of mine, against whom I had played baseball when he was pitching for Lincoln and I was pitching for Fieldston, and who is now a distinguished professor of art history at Stanford, Albert Elsen -- he and I had gone through Columbia together.” 2 In an article in the LA Times, “Hunk” gives further flavor to these personal connections: “The collection is really built on relationships,” says Hunk. “Five of the Abstract Expressionist works here at one time belonged to Bill Rubin, who was chief curator of MOMA. We built that relationship with Bill through Al Elsen. They were classmates at Columbia. He adds, “Bill [Rubin] was interested in selling off his collection. There was a question of ethics here, in selling works that could have gone to the museum, he always said that he had offered them to the museum first.’ Anderson gestures towards the splashy black and white “Figure 8”, 1952 by Franz Kline and “Pink and White Over Red,” 1957 by Mark Rothko.” 3

The group of five paintings that the Andersons acquired from William Rubin were eventually donated to Standford University. The gift from the Andersons totaled 121 artworks, the majority of which were Abstract Expressionist canvases, and to secure the donation, Stanford built a dedicated exhibition space for the collection. Enshrined in the museum are the earlier decisions of Rubin, Anderson and other collectors that had been the first steps in elevating the status of these artworks. Not long after the Anderson Collection at Stanford Unvieristy opened to the public, the curator and writer Kimberley Drew posted an image to her instagram with the caption: “Kenneth Noland, Rose, 1961. One of many works by white men in the collection at Stanford - image description: painting of bullseye with pastel colored rings.” The process of inclusion and exclusion in art history is complicated and begins as soon as an artwork is created. While usually opaque, provenance is an interesting place to look for this causation. The job of art historians to excavate and reveal such nexus is becoming ever more pressing. Annette Michelson’s text serves as vital source material for understanding the limitations of art history and the possibility or impossibility of wider artistic perception.

-Robert McKenzie

1.

Annette Michelsen, “Fashions in Living: An Art Scholar’s Loft: The New York Apartment of William Rubin.” Vogue, March 15, 1967 p.142

I The modern sensibility, in its various humours, aspires to an organic unity. 1 Its image of ideal existence is the seamless fabric of a life in which the tensions and conflicts between pleasure and work are relaxed and resolved. An image of fulfillment as ecstatic has been replaced by one of dedication. Our secular models tend, therefore, to be artists and scholars, in whose lives play and work fuse in a kind of grave abandon. We do somehow manage to believe that for Matisse, paradise was, as he said, simply “work.” The same claims made by a statesman or captain of industry has a slightly less triumphant ring. Combining business with pleasure is not quite the same as creating in delight; it does, however, reflect, through less vividly, the same aspiration.

The architecture of the modern sensibility is, then, the incarnation of that aspiration; its constructions propose a Reconstruction. The fluidity of its interpenetrating spaces reflects the hope that all may once again be related in some generally meaningful way. It is intended both to embody and facilitate an integritiy of obligation and desire, performance and pleasure. Functionalism is really a notion about the relationship between efficiency and delight.

Picture, then, a large, light, fluidly composed space, designed for the living and working activities of a scholar and connoisseur, suggesting a life style predicated upon a complex and intimate professional involvement with one of the grander and more sumptuous of imaginable work tools: a collection of contemporary painting and sculpture which constitutes, as well, a constantly regenerative source of visual and intellectual refreshment.

Mr William Rubin’s newly installed quarters are such a place, and its interest is heightened by the fact that its light, silence, and space are those of a loft - a loft with a difference, to be sure - in that commercial area of lower Broadway to which a cab driver very recently hesitated to take me because it was presumably uninhabited, except for irresponsible types, the sort who “abandon wives and children to go off to the South Seas.” The assertion involved, of course, a complex form of hyperbole and distortion but it did reflect an obscure awareness of the fact that lower Broadway and the area extending south to Houston Street and beyond have become for New York ever so roughly what Montmarte and Montparnasse successively were for Paris. The Neighbourhood is unique in providing the spacious and spatially flexible quarters the artist’s work most generally demands, and Mr. Rubin, who has been predominantly engaged, both as scholar and connoisseur, with the art of the modern world, has there installed his canvases and sculptures, living, so far as possible, amidst the artists who made them.

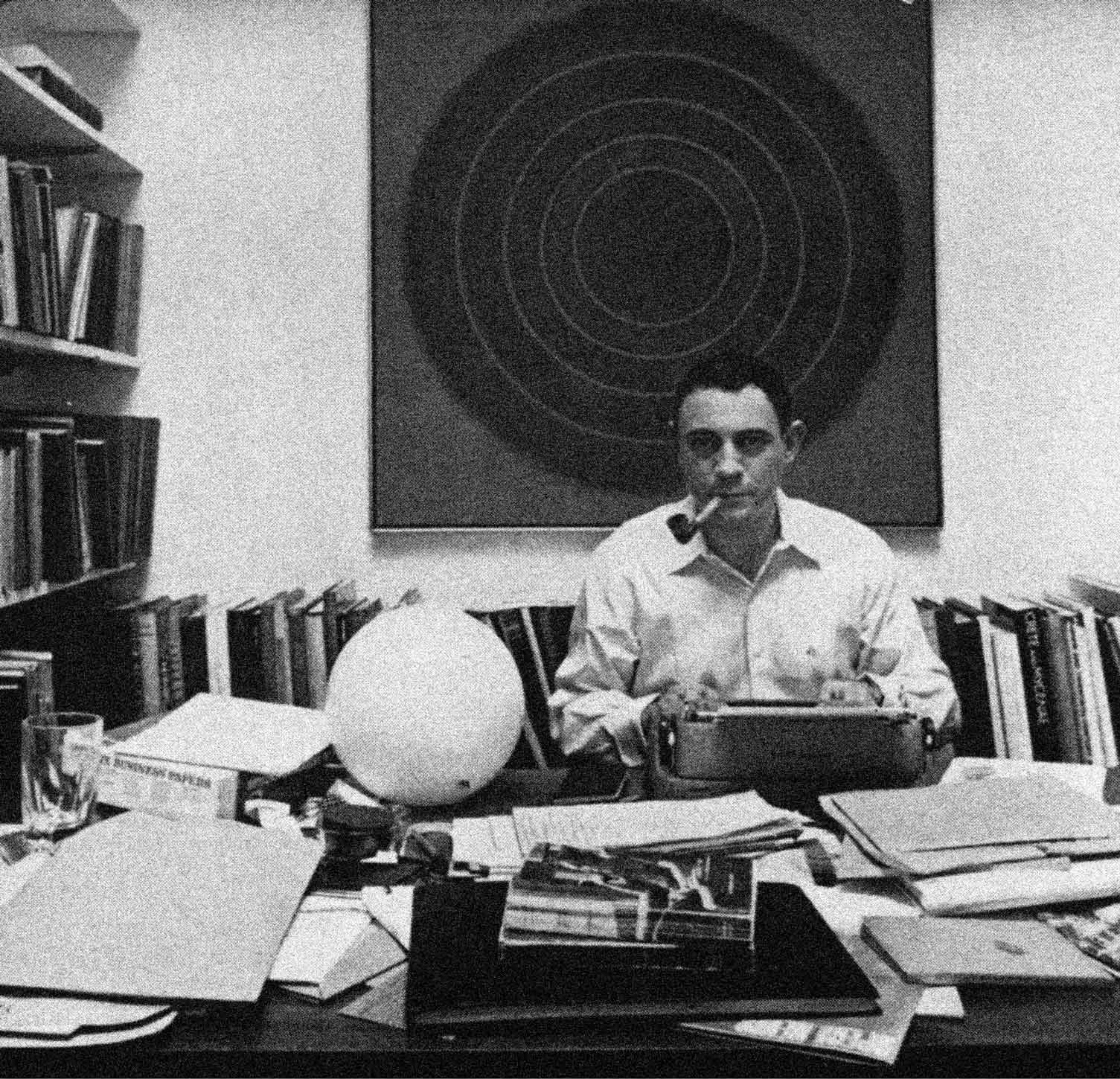

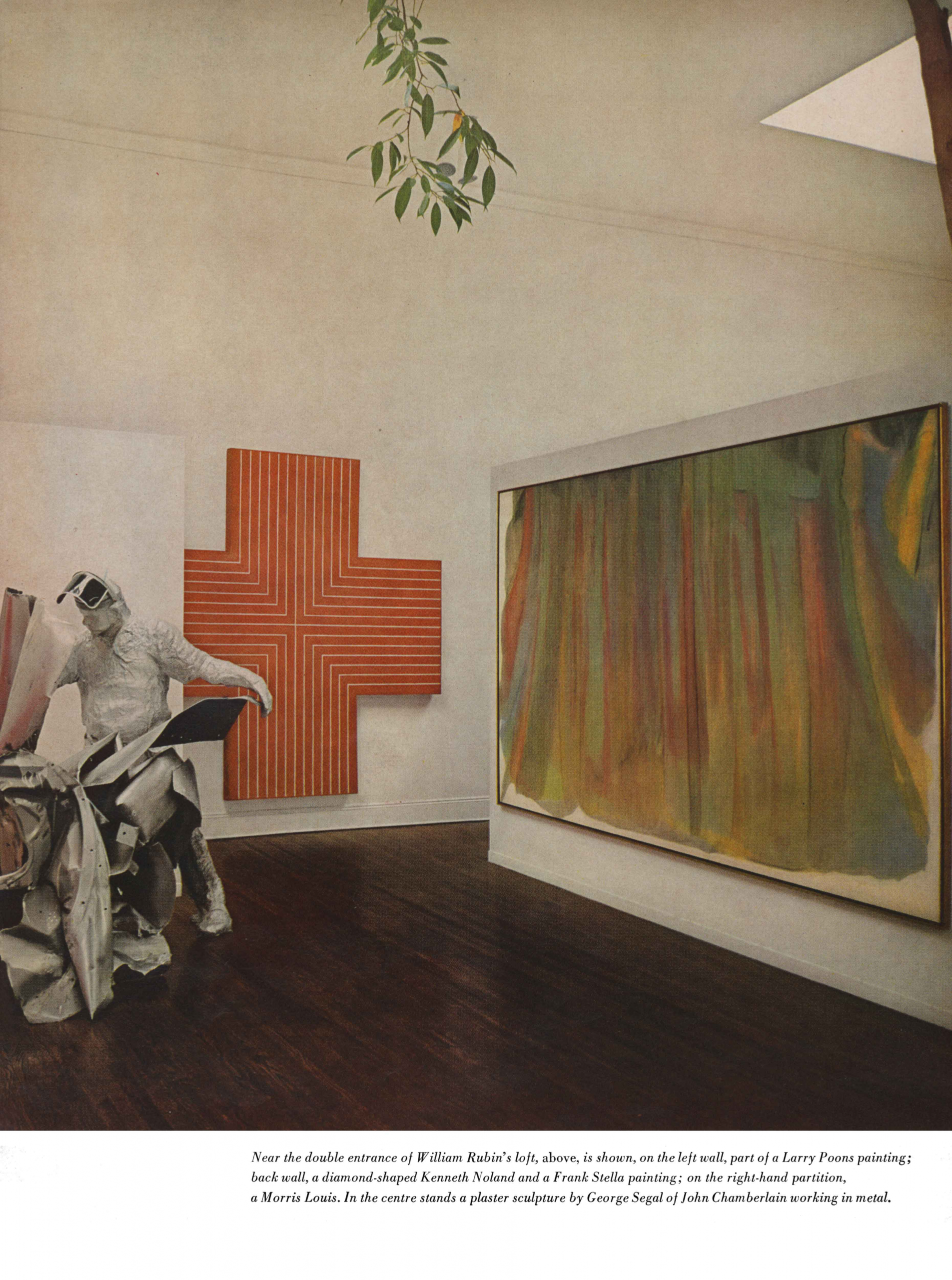

Img:

William Rubin’s Apartment, 1967: The living space-_ on the grand scale but intimate. Above: On the left wall, a Hans Hofmann, a Gotlieb, a de Kooning, and an André Masson; in the corner, a Herbert Ferber sculpture; on the back partition, a Mark Rothko; on the right wall, a Robert Motherwell, a Clyfford Still, and a Jackson Pollock; on the table, a silver sculpture by David Smith.

Photo: William Grigsby, Vogue © Condé Nast

I This choice, and the quite astonishing thoroughness of detail and breadth of scale with which it has been articulated, mirrors both a life style and the desire to restore to the notion of the “studio-apartment,” in an age when it has come to stand for the dreary discomfort of the “one room with wall-kitchen,” some of its earlier charm and nobility. Mr. Rubin’s studio consequently evokes - and quite consciously so - the atelier as it developed in Europe and flowered in the Paris of Impressionism.

One sees, of course, the studios of Vermeer, Teniers, Vanloo and Velázquez in their painting. Examine, however, “Las Meninas” of Velázquez and you perceive that it mirrors a world or arena entirely occupied by model, patron, and artists.

For Bazille, the Impressionist painter, as we see in the paintings of his own studio, the notion of the interpenetration of indoors and outdoors, the opening of the studio to the outside, which of course, a fundamental postulate of Impressionism, is extended by the opening of the studio itself to an outside milieu - to other artists - and to other art forms.

Bazille had this to say: “I’ve diverted myself by painting the studio with my friends present. Manet’s doing me.” And indeed, in “The Artist’s Studio, rue de la Condamine,” the finest Basille’s successive studies of his ateliers in various arrondissements of PAris, Manet and Monet are being shown a canvas by Bazille, Zola leans over the ramp of a wooden staircase to the left and talks to the young Renoir, while, at the far right, Edmond Maître, the cultivated and understanding friend of the group, is playing piano. The studio was described by contemporaries as simple and austere, the home of a “man of purpose and determination,” which is to say a builder, and the spareness of its décor is, indeed, sharply at variance with the taste of middle-class interiors of the time.

There is in the Rubin loft - and down to the detail of the piano - an echo of this intent, of an iconography of fusion, between work and life, openness and intimacy, the personal and social. The unity of feeling which pervades this place - and it is an American place - proceeds most directly, from that education of the eye which has animated the work of the scholar and connoisseur.

Mr. Rubin attended, while at Fieldston School, the classes in painting taught by Victor d’Amico, Director of Education at The Museum of Modern Art. Mr. Rubin started to collect prints when in high school and began to acquire paintings during his senior year at Colombia College. The first of these was a Kirchner, “Woman with Red Flowers.” The early interest in German Expressionism and in other schools of the modern tradition was stimulated by the acquaintance with the late Curt Valentin, whose courtesy, generosity, and scholarship, almost unique among dealers of our time, were responsible for the education of a generation or two of collectors in this country.

After a year of post-graduate musicological study at the University of Paris, Mr. Rubin took a Master’s degree in history at Columbia. The subject of his thesis was Michelet. This was followed by the doctoral studies in art history, concentrated in the study of modern, early Christian, and pre-Renaissance art under Meyer Schapiro and Millard Meiss, which enabled him to begin, at the age of twenty-four, his teaching career at Sarah Lawrence.

The paintings Mr. Rubin bought in the early fifties were largely Expressionist and Surrealist. Some of these were sold or exchanged during the later fifties in order to secure contemporary ones. Others have been given to museums or are still in his possession. It goes without saying that Mr. Rubin deeply admires the work of many contemporaries not represented in his collection, but limitations of money and space - as well as the desire to avoid a “personal museum” - have militated against such acquisitions.

One of the particularly striking aspects of this very particular group of works by major artists involves the manner in which it recapitulates both an expansion of a personal taste and an education of the eye on the one hand and, on the other, the art historical order of the movements represented, from, let us say, André Masson, who stands for Surrealism, through Hoffmann and de Kooning, to Stella, Kelly, Lichtenstein, Noland - as if to confirm one’s belief that taste is necessarily inflected by historical awareness. It was, however, hardley the concept of group, movement, or style as such which have dictated choice, but rather the manner in which an individual canvas challenged the eye.

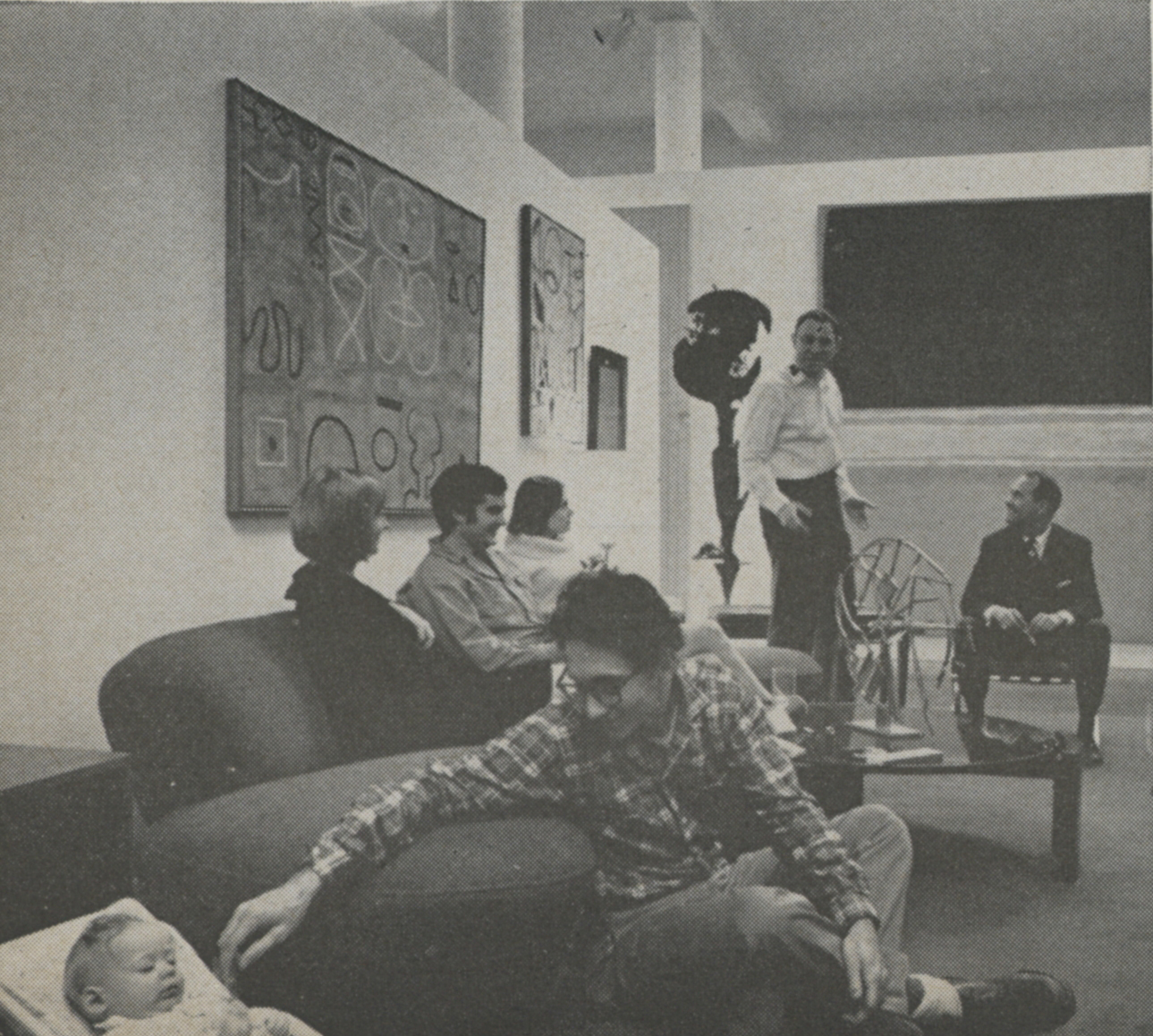

Img:

Artists and friends. On the sofa, Mrs. Frank Stella, Mr. Larry Poons, Miss Lucinda Childs; on the floor, Mr. Frank Stella with baby Michael Stella. Standing, Mr. William Rubin, with Mr. Wilder Green seated,

Photo: William Grigsby, Vogue © Condé Nast

I If one considers the history of significant art as a series of challenges addressed by the artist to himself and, inevitably, to the taste and sensibility of his time, then the collection is seen in its true historical dimension, and the evenness of its extraordinary quality is to be explained by the tenacity with which that challenge is sensed and maintained. The acquisitions correspond to a deep, personal need, are chosen in passion and by a taste which is educated as it chooses: The process is circular, self-perpetuating, self-critical, ad open-ended. It animates, as well, the collection’s physical arrangment, the manner in which hanging, lighting, and grouping heighten or suggest aesthetic, or even historical, relationships.

And this, in turn, is deeply bound up with the spatial architectonics of Mr. Rubin’s over-all conception of a flowing, sky-lit space articulated by free-standing partitions which was realized architecturally by Richard Meier and his assitant, Carl Meinhardt, in dialogue with Mr. Rubin. An architect who is a friend of such painters as Frank Stella and Barnett Newman, Mr. Meier was especially sympathetic to the problems posed by the requirements of setting out the works of art, making the living areas relate to them, and still allowing his architecture an integrity and beauty in its own right.

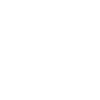

The studio is conceived, then, as far as possible in terms of a constant flow between work and living activities, This is re-inforced by the manner in which, as Mr. Rubin envisioned, kitchen and dining-room space are open to each other, and these two, in turn, open on to a “living and working area,” so that even such household tasks as the preparation of meals can be carried out within full sight of superb canvases.

From the kitchen one sees a Louis, a Rothko, and an Olitski. A sculpture by Stankiewicz, placed immediately next to the work table, echoes the metal of the cooking equipment, “a reminder of the fatality of the kitchen machinery.” These strategies of echo and reflection, of antithesis, and contrast accent the overall conception.

The present installation then involves a major portion - some thing like sixty per cent - of the works of art in Mr. Rubin’s posession. Painting and sculpture reflects his interest, though hardly its full range, and of course the public obligations of lending for major instituional occasions which devolve upon the major collector involve absense, from time to time, of certain works. The Pollock, Still, Kline, the Gottlieb, and a Louis at present hanging, will, for example, be away on loan later this year, and their wall space filled with paintings by other artists.

Among the canvases currently installed but not shown in the accompanying photographs are works by Huot, Kelly, Avedisian, Parker, Reinhardt, Dzubas, Hinman, Youngerman, Jenkins and sculpture by Gabriel Kohn. Two large Caro sculptures are kept on the Sarah Lawrence campus.

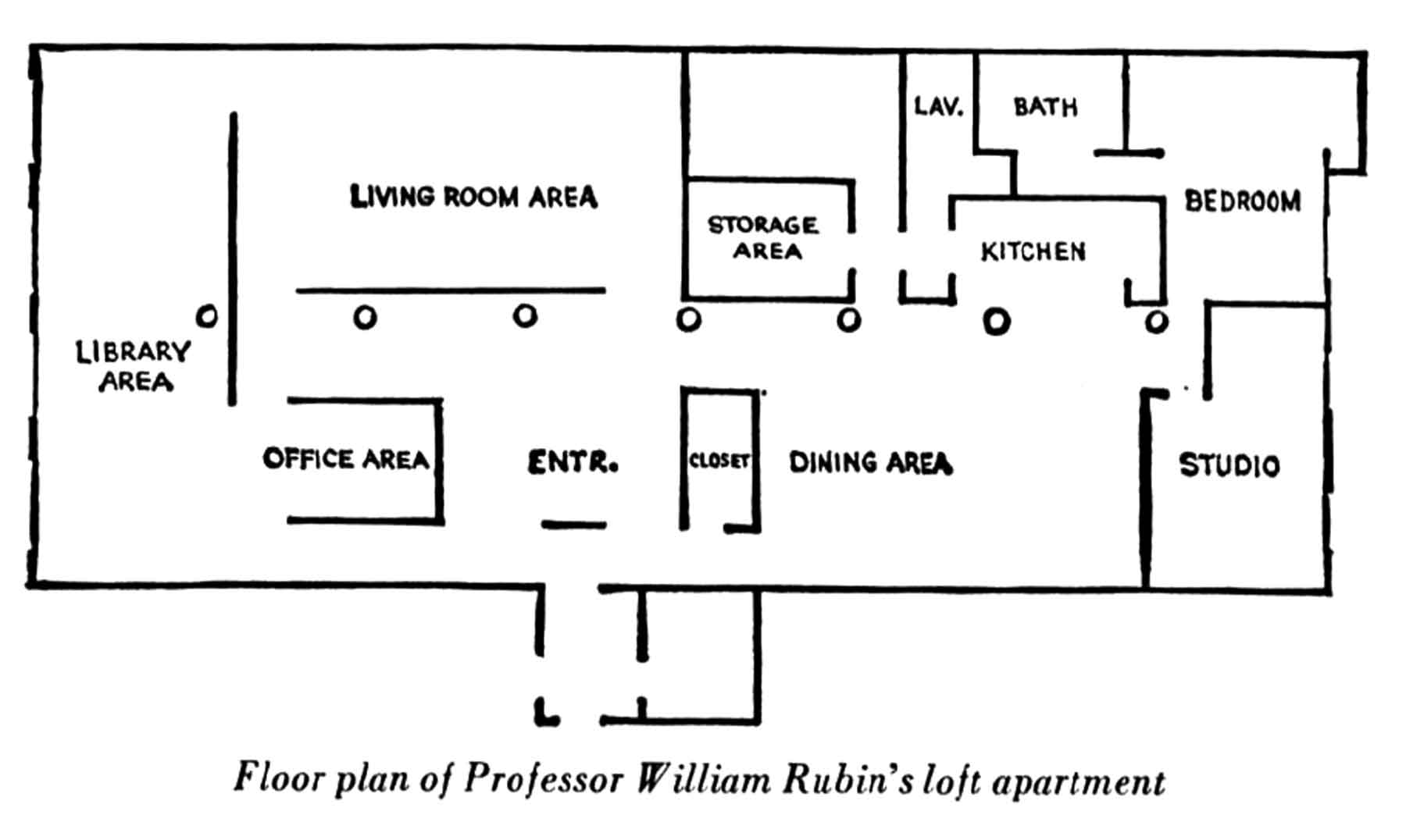

The installation of the collection is mobile and poits up a variety of affinities. The juxtaposition of two paintings by Kline and Newman, each proposing an individual, antithetical use of black and white, provide one indication, among many, of the convergence of taste adn critical insight which informs the installation as a whole. The paintings of Rothko and of Louis (a painter chonologically of the Abstract Expressionist generation who matured, however, relatively late) constitute a kind of historical or stylistic frontier.

It is from the point on that Noland, Stella, Poons, Lichtenstein, and their contemporaries make their entrance into the collection. Their work extends, as it were, one of the most interesting problems in contemporary art, one which has been widely but on the whole, rather loosely discussed: the nature and degree of the relationship between European and American art. The fact is that in a very general sense and until relatively recently, the artists of both continents did share - and this quite apart from differences of style, technique, media or quality - a complex of premises involving an aesthetic of poetic expression.

it was in this sense that the work of Pollock could be said to represent - in its use of automatism, for example, though only in this respect - a transmutation of Surrealist poetic painting, as represented here by Masson, into abstract form. It is certain that the later painting in this collection has offered resistance to the sort of literary exercises performed upon the painting of the forties and fifties.

It is significant that the critical literature on Noland, Stella, and Poons, for example, is more exclusively analytical: its tone is more circumspect and precise, its language more chaste. This is due, in part, to a growing realization that our critical method and categories are badly in need of refining and re-focusing; it seems, as well, a reflection of the work itself.

I The Lichtenstein of this colleciton is the work of the artist who formulated most cogently within the canon of what has been called “Pop Art,” a question about “high art” and its underlying assumptions as they relate to Kitsch. At its best and most interesting, this painting became, in a sense perhaps even deeper and more meaningful than was at first apparent, “an episode in the history of taste,” as it has been termed. It came, of course, as an expression of a certain kind of taste or style, but it represented, too, a challenge to the taste and sensibility, to the manner, aesthetic, the tone and climate of the late fifties. This questioning constitutes its link with the radicalism of the visual syntax of Stella and Noland, among others.

Two major sculptures in the collection are “Australia” and “Timeless Clock” of 1957, the most intricate of David Smith’s graphically conceived works. Sculptural acquisitions include, as well as an Agostini plaster, two important works by Herbert Ferber, Mr. Rubin’s friend and neighbor in the building, and Seymour Lipton. “The Sculptor” (1966) by George Segal, is a portrait of John Chamberlain making a sculpture. Mr. Rubin had seen this work while not quite completed on a visit to Segal’s studio. Although uncertain about it at that time, he found that it “fell into place” once Segal had revised Chamberlain’s piece and had applied aluminum paint.

The gradual revision of judgement accompanies both the process of acquistion and that of conserving the prolonged contact witht he work of art, undoubtedly deepening and clarifying perception. And there is the renewal of pleasure, both sensual and intellectual, which must accompany the return of the painting or sculpture on loan, the perception of art through eyes other than one’s own: those of the seriously committed or interested student, critic, and connoisseur, the visitor from university or museum, American or foreign.

It is Mr. Rubin’s intention to acknowledge, indeed to stress, the metaphor of openness which characterizes a life style as embodied in the collection and its environment, by rendering it accessible to that international community of artist and intellectuals - and, in fact, to the community of all the passionately-interested - whose attentiveness, symptathy, and critical support have fostered and sustained advanced art.

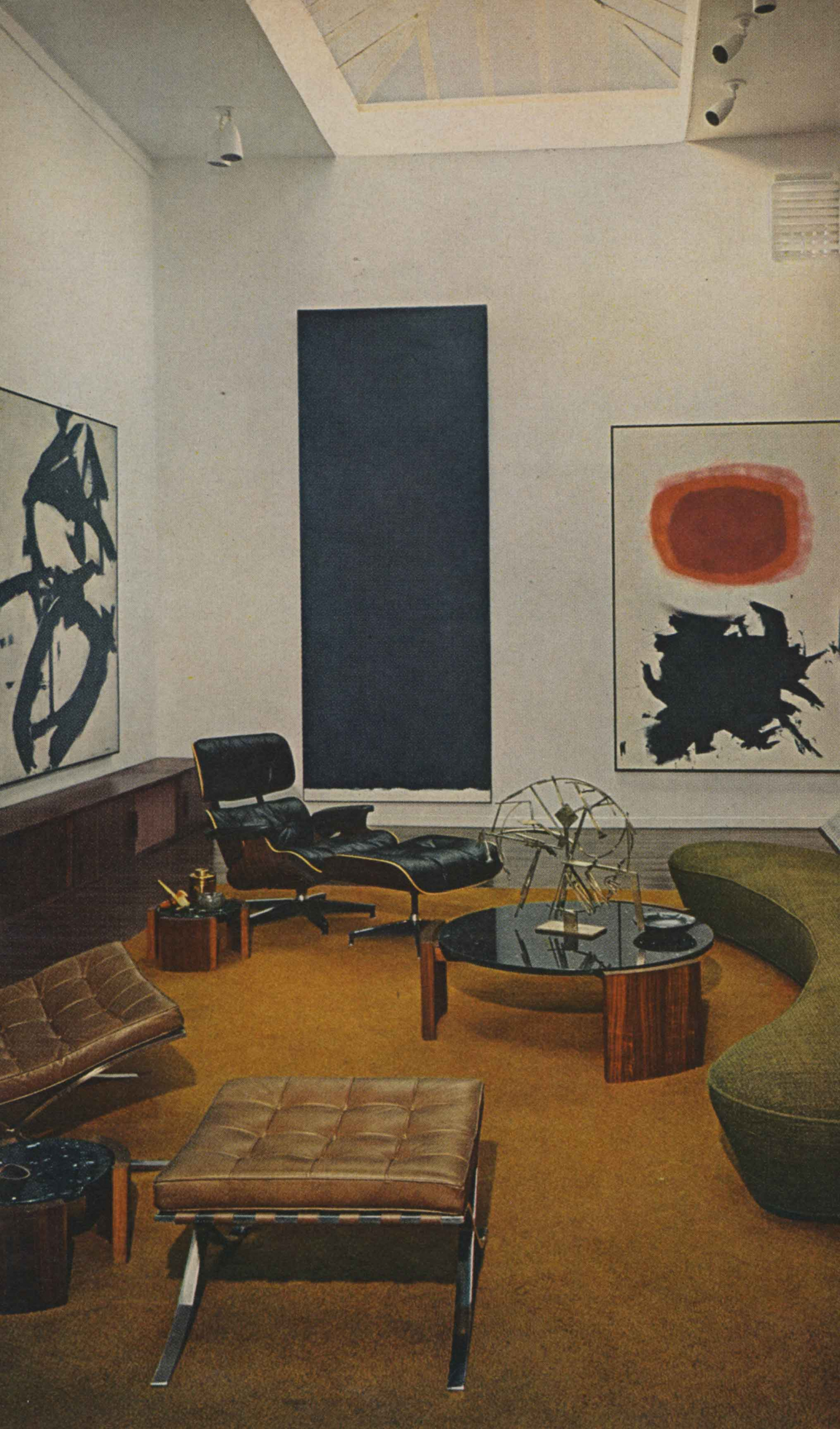

Img:

William Rubin’s Apartment, 1967: Left wall, a Franz Kline; back partition, a Barnett Newman black-and-white painting, and an Adolph Goulieb.

Photo: William Grigsby, Vogue © Condé Nast

↑